Fool me once, shame on you; fool me twice, shame on me. As Latin American markets notch positive year-to-date returns even in the face of the eurozone crisis, this old proverb could yet haunt investors if another global disaster strikes.

Since December, following the European Central Bank’s liquidity operations to ease the eurozone crisis, foreign investors have loaded up on Latin American stocks, currencies and bonds in tandem with the liquidity-fuelled emerging market risk rally.

The Latin credit market has thawed in recent months, opening the gates for bond issuance across all stripes, from sovereign, sub-investment grade corporates to benchmark local currency deals. Meanwhile, the MSCI Brazil index and the S&P Latin American index are up 21.9% and 14.5% year-to-end February, respectively.

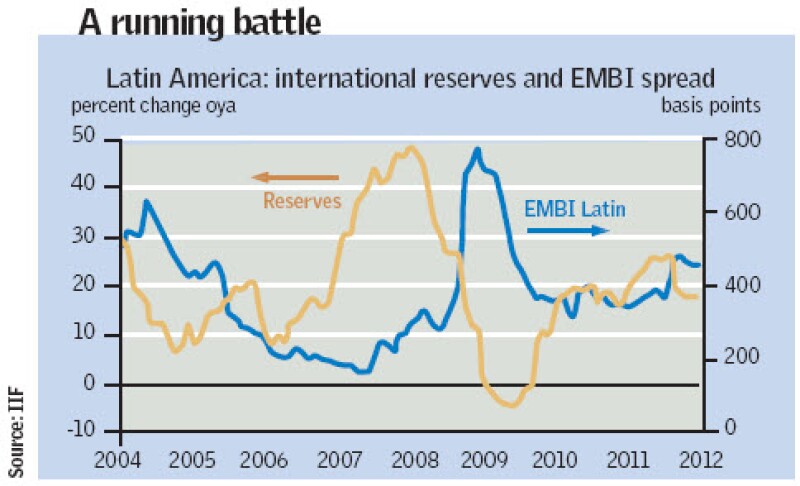

The justification for this portfolio shift in Latin America’s favour is the region’s stronger growth prospects, attractive returns on financial assets and strengthening credit metrics relative to developed world standards. And yet, from 2007 to date, episodic emerging market rallies have taken root only for global economic and market shocks to knock the markets off kilter.

Against this backdrop, risks cloud the Latin American outlook: cheap

liquidity from G4 central banks threatens to destabilize domestic financial markets and trigger export-damaging currency appreciation, while, at the same time, the perennial threat of capital outflows has hardly receded given the global risks. These include another worsening of the European sovereign debt crisis, a Chinese hard landing and lower-than-expected US economic growth.

For now, the market consensus is betting on a modest decline in net private capital inflows to Latin America this year to $250 billion, down from almost $260 billion in 2011 – which was biased towards the first half of the year – according to the Institute for International Finance (IIF).

In a January report, the IIF reckons that a fall in trade financing flows, driven by weaker demand, will offset a moderate recovery in portfolio equity flows. The IIF reckons that capital flows will strengthen to over $270 billion in 2013, as global growth prospects marginally improve.

“So far this year, neither Greek or Portuguese debt fears, nor Iranian nuclear tensions or China growth fears have been capable of materially derailing the Latin American rally,” says Jeff Williams, strategist at Citigroup. But modern emerging market financial history is littered with boom and bust cycles, unnerving those who fear the faster Latin American markets rise amid the eurozone headwinds, the harder they will fall.

Déjà vu moment

“I think I’ve seen this movie before,” Carmen Reinhart, senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, tells Emerging Markets. “An extended period of stable low interest rates in advanced economies has been coupled with a terms-of-trade boom for commodity exporters in Latin America. Cycles, by definition, go up and down and yet, this cycle, by and large, has continued from the spring of 2009.

“And therein lies the danger: markets might come to the same conclusion that this time it’s different and treat the inflow of capital as a permanent feature of the brave new world,” says Reinhart, co-author with economist Kenneth Rogoff of the ground-breaking study of global boom and bust cycles, This time is different.

Recent developments only highlight the volatility of the markets and the risks ahead. As the eurozone sovereign debt crisis intensified in the second half of 2011, banks withdrew funding in international markets, and global deleveraging gathered pace. The subsequent capital flight caught market participants off-guard, with local currency bonds sinking into the red.

Inflation-targeting central banks in Latin America had to cut interest rates given weakening domestic demand. In a dramatic volte-face, the Brazilian real weakened and capital controls were loosened. Even China experienced portfolio outflows and the renminbi weakened.

However, the European Central Bank’s seemingly limitless provision of eurozone banking liquidity in December stemmed the free fall in global markets. In January alone, emerging market equities rallied by 8% while currencies strengthened in tandem with the rally in credit spreads for European financial bonds.

The optimistic view

The MSCI Global Emerging Market index has returned 15.8% year-to-end February, one-third of which is thanks to currency gains. In sum, ECB and US Federal Reserve liquidity measures have created the impression that contagion risk from Greece’s sovereign debt default will be relatively limited while global banking stresses can be contained – for now.

Latin investment bulls argue that asset prices have naturally rebounded this year-to-date – and that the rally has further to go – as the region’s stronger economic fundamentals will draw in strategic inflows from real money investors.

The large economies of Latin America – with the glaring exception of Venezuela and Argentina – boast stronger economic fundamentals: relatively strong public and private balance sheets, a modest chunk of foreign debt, more flexible currencies.

In addition, they have fiscal and monetary space to stabilize their economies in the event of global shocks, though less so than in pre-Lehman crisis days. The improvements in the region’s economic structure helped propel growth to an average 4% between 2004 and 2008, compared with the 2% earlier in the decade and for much of the 1990s.

Adding a sense of momentum to the pitch that economic outperformance should translate to financial market gains, Brazil’s benchmark stock market, the Bovespa, for example, has returned an average 18.5% return per year between 2005 and 2011, even as western economies ground to a halt in 2008.

Any shock to the Latin American market rally will be external rather than domestically driven, many argue. After all, the argument Latin America’s rising relative credit strength and growth prospects would buttress foreign investor positions failed the stress test in the second half of last year.

But a recent study, commissioned by the Washington-based Brookings Institution, showed that economic fundamentals do not seem to matter to a country’s resilience during the outbreak of a severe crisis. This was the case, over the past decade, for Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, Peru and Uruguay, respectively.

The study’s authors, Luciano Cohan, economics professor at the Universidad de Buenos Aires, and Eduardo Levy Yeyati, economics professor at Universidad Torcuato Di Tella, developed a dynamic global risk index – including risk appetite indicators, the price of commodities and global growth projections – to determine the importance of sovereign fundamentals in stemming the risk of capital flight.

“No matter how solid balance of payments and financial balance sheets look in individual countries, capital tends to pull out and currencies sell off everywhere at the same time, and the associated financial panic erodes growth,” says Yeyati. “The market behaviour looks the same as in the early 2000s, despite the fact that these countries have changed financially and economically.”

Nevertheless, better economic fundamentals explain why some countries in Latin America rebound quicker than others.

One explanation for the seeming contradiction between Latin America and the developed world’s relatively decoupled economic fundamentals and the strong recoupling of financial markets in a global shock is down to changes in the financial industry. The globalization of capital markets and new financial products – such as exchange-traded funds – have reinforced the rise of market correlations, by geography and asset type in recent years, says Yeyati.

It’s not just risk management techniques that have driven up correlations. Strategies to outperform the market, known as alpha extraction, have also become a source of volatility for Latin American assets via risk on/off trading techniques, currency carry trades and cross-asset arbitrage techniques.

CAPITAL FLIGHT VULNERABILITIES

What’s more, the vulnerability among South American exporters to capital flight is high given the correlation between high commodity prices, capital flows and domestic credit growth as banks and households lever up in the face of the windfall.

In a bid to stress test the region’s vulnerability to global shocks, Morgan Stanley analysts this year identified those emerging market economies that are, in theory, most exposed to capital outflows, principally in economies that have experienced a surge in portfolio flows while domestic credit growth has outpaced nominal GDP growth.

It concluded that Brazil, Chile and Mexico – in addition to their emerging market counterparts, Turkey, Poland, Czech Republic and Hungary – were most exposed to capital flight.

Meanwhile, Peru and Colombia were seen as least exposed, given the virtually non-existent volume of dollar liabilities, among other factors. Their findings sit awkwardly with the defence buffers in these Latin economies: Brazil’s $356 billion war chest of foreign exchange reserves, Chile’s macroeconomic stabilization fund and its strong pension fund system as well as Mexico’s flexible credit line from the IMF.

But irrespective of the region’s growth outlook or the strength of its policy arsenal to combat a market storm with foreign-exchange reserves, Brazil, Chile and Mexico were seen as most exposed, given the recent surge in portfolio flows and the risk of macroeconomic instability if foreign funding markets shut down.

Crucially, investors are all too often seduced by seemingly benign statistics that tout the low net exposure to external dollar debt by the public or private sector in these economies, says Patryk Drozdzik, economist at Morgan Stanley. “It’s the gross exposure that provides a source of real risk,” he says.

In Brazil, vulnerabilities are growing. A non-trivial proportion of portfolio flows has been disguised as foreign direct investment (FDI) flows to avoid the portfolio transaction tax, Yeyati fears. What’s more, the composition of Brazil’s FDI investment adds to its vulnerability, since the majority of this investment is concentrated in the highly cyclical commodities sector.

In addition, in the equity market, foreigners accounted for 40% of the turnover of the benchmark Bovespa bourse as of end-February, the highest figure for over six years and above the five-year average of 36%. The combination of new money and relatively high foreign investor positioning could exacerbate losses in a global sell-off.

Latin American observers fear markets could soon be poised on a knife edge given potential global economic shocks. The trigger varies between tighter monetary policy in the West, a resumption of a full-blown eurozone crisis and the China growth question.

Consensus opinion is more sanguine on G4 monetary policies. Although there is a strong correlation between easy monetary policy and asset price reflation, it’s unlikely that recent expansions in the ECB’s and the Fed’s balance sheets have been used to finance trades in emerging markets directly.

For example, Barclays Capital analysts estimate that just Eu50 billion of the net new borrowing of eurozone banks under the first round of the ECB’s long-term financing operations (LTRO) was used for carry-trade purposes that might have found its way into emerging markets.

Instead, the liquidity-boosting measures have been designed to shore up western bank solvency and have thereby only indirectly boosted emerging market sentiment.

Another risk is that the ECB’s monetary relief effort ultimately fails to shore up eurozone sovereign and bank funding markets, heaping on the risk of indiscriminate capital flight out of Latin America in a panic sell-off – though most agree that such a scenario now seems remote.

For the longer term, the bigger worry is the projected slowdown in Chinese growth to 7–8% in the coming decade, from the 10.7% recorded in the previous decade, a development that would reduce the superpower’s commodity import demand and the region’s terms-of-trade position.

That prospect has unnerved some analysts. “If you start considering a scenario where China starts growing at 7% and it changes its growth model in favour of more inward economic activity, then it’s not obvious that support for capital inflows into Brazil is as strong as it has been last decade,” says Yeyati.

The market impact could be profound; commodity companies alone account for half of the Bovespa’s capitalization.