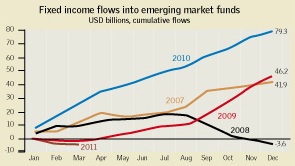

Volatility has returned full force to emerging bond markets. Growing concerns over inflation, commodity prices and the strength of the global recovery – together with a renewed geopolitical turmoil – have contributed to a reversal of flows from emerging market bond funds in recent weeks, with consecutive weeks of outflows contrasting with the $35 billion that had gone into these funds in 2010.

Yet far from heading for the exit, traders in Latin American debt remain by and large undeterred. Only high beta names such as Argentina markedly sold off in February, while trading in many Latin American oil exporting countries, such as Venezuela, Mexico and Colombia, was buoyed by the high oil price.

As a result, according to data from global fund tracker EPFR, while $1.4 billion was withdrawn from emerging market bond funds during the six weeks to March 14, net bond outflows from Latin America over the same period totalled just $9.55 million.

Ten years ago, emerging market bond traders were calling for others to recognize that Latin American debt was hugely undervalued. Now, rather than having to pitch the investment case for Latin debt, that same group is looking at the tight margins of Brazilian credits and wondering where the value has gone as the asset class goes mainstream.

PRIMARY ISSUES

Primary issuance of Latin American bonds has been unremitting, with $27.4 billion of bonds from Latin American issuers since the start of the year in well over 40 deals. Brazil has been responsible for 45% of that by volume through 18 deals, including a huge $6 billion note from Petrobras.

Syndicate officials and analysts expect primary issuance of hard currency bonds from Latin America to remain healthy this year. The region’s big markets – including Brazil, Mexico and Colombia – are likely to provide the most active Latin American primary bond market supply, say syndicate officials.

“The fundamentals in Latin America are strong if you compare them to western Europe, for example,” says Katia Bouazza, head of global capital markets, Latin America, at HSBC in New York. “Investors are attracted by the oil and commodity prices. And if you compare them to other emerging market countries, for example the Middle East at the moment, the political backdrop also looks stable.”

For now, fund managers and traders are shrugging off fears over the longer-term impact of sustained high oil prices on global economic growth. For Latin America, the consensus is that a prolonged oil price shock could be a boon for the region’s oil producers. Brent crude was tracking at just under $115 a barrel as Emerging Markets went to press on March 22, having risen over $20 since mid-December amid concerns over oil supply from North Africa and the Middle East.

WHO’S ISSUED WHAT?

For many countries in Latin America, heightened demand from domestic accounts continues to consume primary market bond supply.

“There’s been an explosion of domestic demand in Latin America,” says Max Volkov, managing director in Latin American debt capital markets at Bank of America Merrill Lynch in New York. “The amount of money local pension funds have in Chile, Peru, Colombia, Mexico and Brazil are multiples of what we saw three to five years ago, and these local investors are becoming major participants in the primary and secondary markets.”

Peru sold a $1.5 billion sol-denominated bond last November – $1billion of which was snapped up by Peruvian investors.

TOO TIGHT TO TEMPT

But Brazilian credit’s tight margins may not be sustainable, as some say that the current risk-reward ratio is not attractive. Investors are becoming increasingly concerned about those valuations, with the anticipation that their demands to be paid better for the risk have not yet been priced in.

Those investors are differentiating between credits rather than buying into bonds in the herd mentality displayed at the end of last year, when emerging market bond funds were flush with cash following a year in which emerging market bond prices soared.

Yet syndicate officials say that despite the complaints, deals for Brazilian issuers continue to be easy successes.

“In Brazil, I see no slowdown for deal appetite,” says Bouazza. “Deals are continually well oversubscribed, and although you hear investors saying that the yields on some of these notes are too tight, that trend doesn’t seem to be translating into investors not buying the deals.”

Primary supply, especially from debut issuers, at least offers a new issue premium which secondary trading does not. And with issues expected this year from telcos, homebuilders, car rental companies, retailers, the oil service sector and infrastructure companies, investors have plenty to choose from.

“Yields are so tight in Brazil that I’m not spending a lot of time hunting around for secondary market opportunities – there are always some opportunities, but for that country, new issuers offering a new issue premium are the most likely to look cheap,” says Ray Zucaro, portfolio manager at SW Asset Management in California.

But those still ploughing money into Brazilian debt say that although Latin American secondary bond markets show tight yields, the tight margins are not specific to Brazil or Latin America, with US high-yield names also trading close to historically tight levels. A BB rated index of US high-yield bonds trades around 5.82%, compared to a 10-year average of 7.98%. The same for a single-B rated corporate index is around 6.74%, much tighter than the 10-year average of 9.81%.

Although the country’s debt is trading at levels even tighter than five years ago – its implied 10-year yield was around 6–7% from 2006 to 2007, and is now around 4.6% – the credit has improved, say some analysts, making those tighter spreads justified.

This is thanks to stronger company balance sheets and lower political risk, especially in Brazil, analysts say. They also say there are ample opportunities in the likes of Argentina and Venezuela for those who prefer their bonds with a little more risk and a little more reward – while Brazil five-year CDS was trading around 111bp in mid-March and Mexico’s at 105bp, Venezuela’s was at 1067bp and Argentina’s at 598bp.

Even rising inflation has failed to perturb investors in Latin American dollar bonds.

“A substantial part of inflation is explained by a change in relative prices at a global level, namely commodities prices increasing versus industrial manufacturers,” says Santiago Cuneo, an economist at SW Asset Management. “This change in the terms of trade actually benefits emerging market countries as most are commodity producers.”

And while inflation erodes competitiveness, it also increases tax collections, so it is positive in terms of fiscal solvency as long as external accounts are sustainable.

“Inflation isn’t as scary for fixed income investors in the emerging markets as in the developed world, because most investors actually care about returns translated into US dollar terms rather than in real terms,” says Cuneo.

But investors have also taken heart that the central banks in Latin America are willing to tighten monetary policy to contain inflation. Monetary authorities in Brazil, Colombia, Peru and Chile have all hiked interest rates this year – Brazil’s base rate stands at 11.75%, Colombia’s at 3.25%, Chile’s at 4% and Peru’s at 3.75%. While inflation is exceeding targets, the deviation from those targets is not too alarming at 100bp–150bp over, keeping a lid on major concerns. Inflation in Brazil is at 6%, for example.

DOMESTIC DEBT

|

But for local currency bonds, concern about inflation eating into returns is more acute and strikes at a lower level. Last year investors brayed for increasingly more local currency debt, as foreign investors looked for enhanced yields by way of currency risk and appreciation, and enthusiastically bought local currency bonds hoping for a way to avoid volatility in the dollar. They also extolled the virtues of companies that had local currency assets borrowing in their local currencies, thus reducing their risks. This year, while some enthusiasm for local-currency debt remains, fear over rising interest rates has prompted a partial sell-off.

“In an environment of rising rates, the local LatAm curves have taken massive hits over the last few months,” says Juan Cruz, head of emerging markets credit research at Barclays Capital in New York. “Some of the investor focus is being taken off local-currency bonds because of that.”

But since early 2010 the inflows of hard-currency funds into local-currency funds have more than doubled, with investors attracted by the high nominal rates of return. Instead of outflows, the focus has shifted to shorter durations rather than away from local currency bonds entirely.

|

Before inflationary pressures grew in the second half of last year, demand was great for local currency bonds extending to 10 years. Over the last six months, the demand has increased for three- to five-year durations. It is hard to find a dent in the bullishness of Latin American debt investors, even from those that can short this debt. Few see the strength of the Latin American bond market, built so rapidly over the last 10 years, waning. Some acknowledge the oil price and inflation risks, but even still, only a fundamental credit event – either in or outside emerging markets – is likely to deter investors in this region.

But with the collapse of Lehman Brothers having blown air into what could well be a bubble for emerging market debt, and investors shrugging off a political crisis – and now war – in the Middle East and North Africa, a catastrophe large enough to deter investors from the Latin American bond market still seems a long way off.