The International Finance Corp has brought to fruition a project it has been working on for more than two years — to launch its first securitization. The $510m deal achieves capital relief for the IFC and furthers its mission to attract private sector investors to development finance.

“We couldn’t be happier,” said Kruskaia Sierra-Escalante, senior manager and global head of co-investor solutions at the IFC in Washington, after the deal was priced in September. “It was a pilot transaction, and a very successful one.”

For the African Development Bank, which launched the first securitization by an MDB in recent times in 2018, and the Inter-American Development Bank, which brought a major transaction last year, the principal motivation was capital relief.

That is essential to the IFC’s deal too, but its main aim was to mobilise private sector investors.

“We want the ambition of helping create a new asset class, to expand the investor universe to investors which are not generally taking risk on emerging markets,” said Sierra-Escalante. “That is the place we are coming from. This does release capital, but the primary objective was increasing the likelihood that investors will look at this as a new asset class and feel comfortable, and will continue to invest.”

Full capital stack

For this reason, the deal, IFC Emerging Markets Securitization 2025-1 Ltd, is the first by a major MDB in recent years in which the senior notes were placed with investors, as well as the mezzanine tranche.

Achieving a true sale structure was more difficult than a synthetic securitization, because of the legal complexity of transferring assets. But the IFC was determined to bring in investors at large scale, not just the specialists who buy synthetic securitization mezzanine tranches. The deal needed to have a big senior tranche, partly to make it worthwhile for those investors.

Goldman Sachs was the arranger.

IFC will remain the lender of record and servicer for all the loans, but participate 100% of the economic ownership to the special purpose vehicle.

The $320m ‘A’ class was rated Aaa by Moody’s and placed privately at 130bp over Sofr. This is the top 62.8% of the structure.

Beneath that is an unrated ‘B’ mezzanine tranche of $130m, which is the middle 25.5% slice. It pays 220bp over Sofr, but was retained by the IFC. It was then insured on an unfunded basis by a consortium of credit insurers. The insurance premium was negotiated outside the structure, and not disclosed.

The residual $59.53m equity layer is structured as preference shares, and is the bottom 11.7%. The IFC is retaining most of this, but there is also an outside investor.

The portfolio is static, so the deal will amortise as the underlying loans do, sequentially from the top tranche down. The average life is expected to be about 3.3 years, and the deal has a legal maturity of around 10.3 years.

Diverse portfolio

The pool for the inaugural deal is loans to 57 obligors. Most are unrated but Moody’s has assessed them based on the IFC’s internal ratings.

They range in credit quality from the equivalent of B3 to investment grade, on Moody’s scale, but the weighted average is speculative grade.

“At IFC we are global in emerging markets, so we have been able to have a very nice diversification,” said Sierra-Escalante. “We have also been able to do sector diversification, including some sectors where job creation is at the core, like manufacturing and infrastructure. There are also transactions from our financial institutions group, through which smaller companies can be reached. There are different credit qualities across the portfolio — we have not only handpicked one type.”

Compared with the IFC’s whole portfolio, where loans to financial institutions are a large share, that sector has a lighter weighting in the securitization.

About 55% of the collateral is senior secured loans and 45% senior unsecured. The loans have been made in 28 countries in Asia, the Middle East, north Africa, south and north America, sub-Saharan Africa and Europe, according to Moody’s presale report.

The loans are in dollars, which Moody’s sees as a positive.

Joining the CLO market

Since the top tranche is a true sale, cash securitization, it can be compared with ordinary commercial collateralised loan obligations, which are typically backed by speculative grade US or European ‘broadly syndicated’ leveraged loans (BSL).

Rabih Kanaan, the IFC’s transaction lead on the deal, said: “Unlike a typical broadly syndicated loan CLO where there is a sliver of triple-C risk, we are not putting in anything triple-C, so it’s a higher credit quality.”

Moody’s said the top five country exposures were Turkey (13.4% of the pool, Ba3 foreign currency country ceiling), Mexico (10.3%, A1 ceiling), Bangladesh (6.1%, B2), Brazil (6.0%, Baa1) and Egypt (6.0%, B3).

The credit enhancement for the ‘A’ notes is 36%, which greatly exceeds the exposure to any single country.

Finding new investors

The credit insurance tranche has precedents in deals by the AfDB and IDB, and there is an established group of about 10 major insurance providers that engage in emerging market credit insurance.

But triple-A rated senior notes of an MDB securitization are an unusual instrument that does not appeal to all investors.

The IFC was pleased with the investors it managed to attract.

“Because it’s an emerging market CLO it requires an investor that has sophistication and comfort with emerging market risk, as well as being familiar with structured finance and CLOs,” said Kanaan.

He added: “We priced very competitively for a first time issuer with emerging market collateral. We got [the pricing] anchored in BSL CLOs, which is where we wanted to be, but we’re not stopping there. Our ambition is to go through the [BSL CLO] curve. We believe the credit quality is better than a BSL CLO, so we think we should be compensated with tighter spreads over time.”

Plans for more

The IFC has been known to be contemplating a full capital stack securitization since at least last year, an approach that puzzled some market participants, who wondered how the deal could be worthwhile if the IFC was having to pay investors at every level.

The spread on the triple-A notes is much higher than the IFC would pay on its own triple-A senior unsecured bonds. But the securitization does leave the IFC with excess spread as return on the equity, after paying the senior and mezzanine investors.

The MDB has not revealed how much capital relief the deal obtains. The AfDB’s first deal in 2018 transferred the risk layers from a 2% attachment point to 27.25% on a $1bn portfolio of 40 loans to banks, project finance vehicles and companies. It achieved 65% capital relief.

The IDB’s deal transferred the risk slice from 2.8% to 13% on a $1bn portfolio, freeing up 50% of the capital.

Compared with those deals, the IFC’s has a much thicker equity layer of 11.7%, but all the risk above that is shed.

The IFC has achieved a balance between the degree of capital relief on the portfolio and the share of its income it has given up — which was its aim.

The IFC intends this to be the first of a programme of issuance, branded as Emerging Markets Securitization Programme (EMSP). At earlier stages of its development, the scheme was called the Warehouse Enabled Securitization Programme (WESP).

The IFC invited firms to tender for the role of financial adviser on the WESP in June 2023, intending it to “co-finance new loans by MDBs at origination, with the intention of only holding the loans until they could be packaged and transformed into investable securities for institutional investors.”

The term ‘warehouse’ implies that assets can be assembled, ready to be securitized in future deals, but does not mean there will be a warehouse funding line from external lenders, since the IFC can fund itself with triple-A bonds.

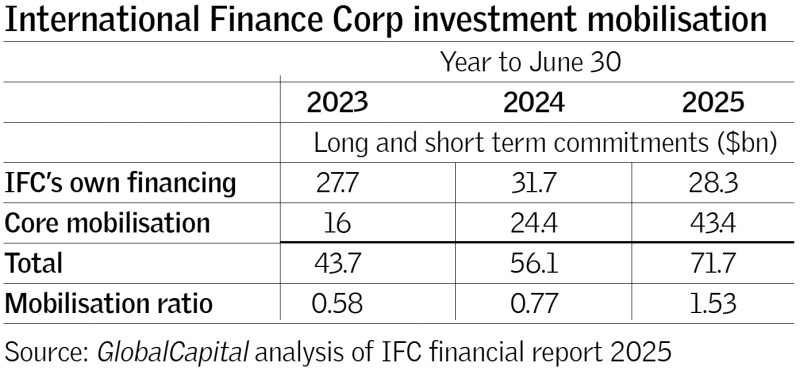

The IFC sees the securitization partly as a way to further its agenda of increasing private sector mobilisation — the amount of private investment unlocked by each dollar of IFC lending.

Alfonso Mora, the IFC’s vice-president for Europe, Latin America and the Caribbean, told GlobalMarkets’ sister publication GlobalCapital in 2024: “We used to mobilise 0.9 times what we invested. The objective is to take that to 1.5 to 2. How can we mobilise two times? We need new solutions.”

One of those has now appeared. The IFC intends to issue at least once a year and has an aspiration in due course for other development banks to be able to use the programme too.

“It’s our ambition to create a solid programme and hopefully others will start replicating,” said Sierra-Escalante. “This is a more complex structure, but brings in a new class of investors. The expectation is we will be able to come with a regular cadence of issuances.”