Just over 80 years ago as the economic brains of the Allied powers were forging an International Monetary Fund to bring financial stability after the chaos and horror of the Second World War, one priority was the need for free and open trade.

The Articles of Agreement of December 27, 1945 declared that the Fund’s second purpose was to “facilitate the expansion and balanced growth of international trade”.

Fast forward eight decades and the issue likely to dominate this week’s Annual Meetings is the US government’s trade tariff policies and the economic disruption they are causing.

Nearly nine months after President Donald Trump’s second term began, the likely impact of his sweeping trade measures is still not clear, partly because they have changed so often.

But every one of the IMF’s 190 member countries is affected, so trade will be top of the agenda for finance ministers, central bankers and development officials as they gather in Washington this week.

Despite some rolling back of tariffs in recent months — earning the acronym of Taco or ‘Trump always chickens out’ — US effective tariff rates stand at historically high levels of about 17% as a trade-weighted average, down from a peak of 25% earlier this year but up from 3% at the start of the year.

While Trump has paused many planned measures, de-escalated his trade war with China in May, and reached deals with partners including the UK, European Union and Japan, the cumulative impact is already reshaping global trade flows in ways economists are scrambling to understand.

The tariffs have not set off an economic disaster. For the EU, for example, at the end of September, economists at ING said front-loading at the start of the year had helped sustain exports to the US. “However,” it added, “we expect EU exports to the US to decelerate as tariffs begin to bite, reinforcing our call of a direct GDP impact of -0.3% in the short run, with significant risks to growth in the longer run.”

Volatility continues. Even after the two parties agreed a trade deal in July, highly favourable to the US, the US has increased tariffs on a variety of products and threatened a 100% levy on pharmaceuticals.

After extreme swings in the US stance, Mexico now has quite a bearable deal, with an effective tariff rate of 7%, so it may even take market share in US imports from China. But Vanguard economists still predict GDP growth of 0.75% at best this year.

The European Central Bank has warned that tariffs could distort production patterns and supply chains, resulting in a less efficient global economy. Some Asian economies are benefiting from trade diverted from China, while others face new competitive pressures in their domestic markets.

In Latin America and Africa, some resource-rich states may benefit from increased demand as global supply chains diversify, while others could lose access to key markets.

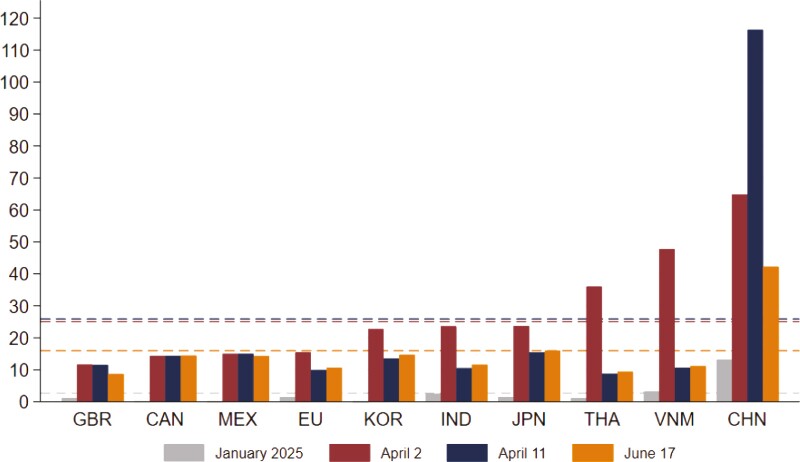

US tariff rates (%)

Import-weighted rates for the 10 largest exporters to the US

Source: Lorenzo Rotunno and Michele Ruta, Trade Partners’ Responses to US Tariffs, IMF, July 2025

Unappealing choices

Research by IMF economists Lorenzo Rotunno and Michele Ruta suggests that countries have options for responding to tariff pressures, but each carries its own economic and political costs.

Retaliatory tariffs may be politically satisfying but can end up just harming domestic consumers and businesses. Industrial policy interventions can protect specific sectors but may distort resource allocation and create inefficiencies. Regional trade agreements offer alternative market access but could fragment the global economy further.

Meanwhile, the uncertainty about trade policy amplifies the negative effects of tariffs, creating a climate in which businesses delay investment.

The relationship under most scrutiny will be the US and China. Although the extreme tariff rates of as much as 145% imposed during the two countries’ tit-for-tat battle in the spring have subsided, the average US levy on Chinese goods is now around 58%, according to the Peterson Institute of International Economics, while China charges about 33% on the US goods it imports. These barriers to trade are unprecedented in modern times.

Rejecting imbalance

IMF analysis points to “mostly adverse consequences of protectionism… in aggregate and across sectors and regions”.

While this view will likely feature prominently in discussions in Washington this week, fundamentally, the US sees it differently.

Scott Bessent, the US treasury secretary, laid out his view of the IMF clearly in a speech at the Institute of International Finance in April. The IMF’s job is to promote balance, he argued, but “everywhere we look across the international economic system today, we see imbalance,” nowhere more than in trade.

“We will not abide the IMF failing to critique the countries that need it most — principally, surplus countries,” Bessent said. “The IMF needs to call out countries like China that have pursued globally distortive policies and opaque currency practices for many decades.”

China, he said, “is in need of a rebalancing. Recent data shows the Chinese economy tilting even further away from consumption toward manufacturing. China’s economic system, with growth driven by manufacturing exports, will continue to create even more serious imbalances with its trading partners if the status quo is allowed to continue.”

More than tariffs

It is not only Trump supporters who believe he has a point.

Michael Pettis, a finance professor at Peking University and senior associate at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, wrote in the IMF magazine Finance & Development on the eve of the meetings that “Rather than railing against tariffs, the world needs a broader conception of trade policy — one that moves beyond the surface-level debate over tariffs and looks inward at how economies allocate income.”

Trade imbalances, he argued, are swelled by a slew of national economic policies that, like tariffs, shift income from consumers to producers — from holding down the currency value to tax subsidies for producers; from wage repression to low interest rates.

“If trade imbalances are ultimately the result of internal choices about who gets what, then fixing them will require more than bilateral deals or protectionist gestures,” Pettis wrote. “It requires a change in how countries structure their economies. It requires power and resources to shift toward those whose spending drives sustainable demand.”

Whether the IMF can shift this debate is questionable. On one hand, Dan Katz, Bessent’s chief of staff, has just taken office as the Fund’s first deputy managing director, making him number two to overall chief Kristalina Georgieva.

On the other, China is an influential member of the IMF, which is looking to increase its clout there, not be pushed around.

After two successive General Reviews of Quotas, the most recent in 2023, failed to alter voting shares at the Fund, leaving emerging and developing countries with just 40% of votes, though they produce 60% of world GDP, China is long overdue an upgrade.

If the coming 17th Review, scheduled to conclude in 2028, also fails to alter quotas, it would damage the IMF’s legitimacy and standing in the global financial system, analysts at Boston University have warned.

Treading on eggshells

Navigating between these competing interests while maintaining the IMF’s credibility as an impartial arbiter of global economic policy will test Georgieva’s diplomatic skills as never before.

The world’s finance officials urgently want the IMF to help develop concrete responses to the trade policy challenges reshaping the global economy.

To meet that need, the IMF’s traditional tools — surveillance, lending and technical assistance — may need adapting to a new world where trade policy has become weaponised.

The immediate task for this week’s meeting will be trying to lessen the economic disruption caused by trade rivalry, while working to prevent further fragmentation of the global economy.

This will require delicate dialogue and possibly innovative policy approaches that acknowledge the new realities of economic nationalism, while preserving the benefits of cooperation.

Maintaining the IMF’s relevance and effectiveness in this environment depends on providing honest assessments of the costs and benefits of different policy approaches, even when those assessments may be politically uncomfortable for major shareholders.

The stakes are high. The IMF’s research suggests the shift toward protectionism carries significant economic costs that will ultimately be borne by businesses and consumers around the world.

Whether this week can generate momentum toward more consensus and lower trade barriers may well determine the trajectory of global economic growth in the next few years.

Swapping over

One irony of today’s debacle for economic historians is that roles have been reversed.

During the negotiations about setting up the Fund, John Maynard Keynes, the British economist, was keen to maintain the UK’s preferential trading relationships within its empire and currency area.

Harry Dexter White, his American counterpart, regarded liberalising trade as the paramount objective — hardly surprising, since the US was keen to access commercial opportunities within Britain’s sphere of influence.

In this, the US was grasping the torch of free trade, brandished so vigorously by the UK in the 19th century, when its industry was supreme and had no fear of competition.

How did it work out? Eighty years later, the US has done very well out of liberalised trade, being still the world’s largest economy by a considerable margin. The US cut average tariffs sharply from 10%-12% in the late 1940s to around 3% before Trump took office.

The UK, on the other hand, has fallen from second to sixth, overtaken by its former colony India.

Nevertheless, the US is unhappy with its lot. As Bessent put it in April: “Intentional policy choices by other countries have hollowed out America’s manufacturing sector and undermined our critical supply chains, putting our national and economic security at risk.”

The current US stance has much more in common with the Britain of 1945, fearfully trying to fend off decline, than the Britain of 1850, confident in its industrial strength.

For the time being, the world economy is coping with higher US tariffs. The IMF’s ability to influence US policy is minimal.

But few of the Fund and member state officials who huddle in the meeting rooms of the IMF this week will have much confidence that taxing trade is going to boost world trade, or the US’s share of it.