Supply disruption concerns have triggered a jump in oil prices year-to-date, with Brent crude prices hitting a ten-month high of $125 per barrel (pb) on Friday amid US and European sanctions on Iranian oil shipments. Even with Saudi Arabia ramping up production, fears are growing that oil prices will remain at stressed levels, as Western confrontation with Iran shows no sign of abating.

Conventional wisdom states oil prices above $100pb typically undermines the global business cycle. And last year's oil price spike, triggered by Arab uprisings, wrecked havoc on oil-importing economies, with their currencies and stocks vastly under-performing exporting peers.And that raises a pressing question: Just how high do oil prices need to go again to eat into growth in emerging markets?

Jonathan Anderson, chief emerging markets economist at UBS, has turned his attention to just that problem - and comes to a relatively optimistic conclusion. He says that average crude prices of around $135pb for the rest of 2012 as a whole and nearly $150pb through 2013 would cause the firm's analysts to re-assess their EM growth calculations. But even then “it would take much higher prices to get us to start “freaking out” about the effects on an EM-wide basis.”

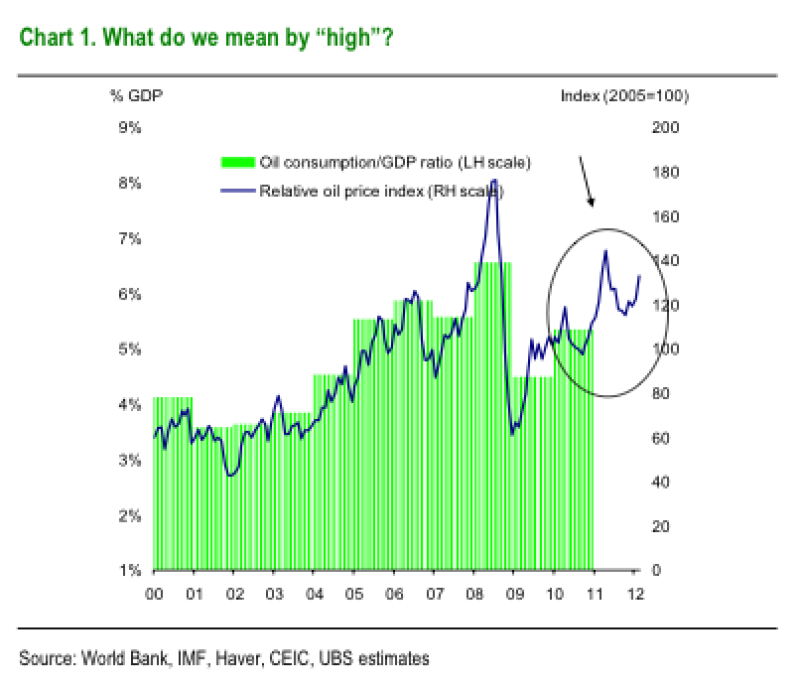

The reason he remains sanguine about the impact of higher oil prices now versus 2006, for example, is that emerging market GDP has been expanding in both real and dollar terms in recent years at a faster rate than EM oil consumption, thereby reducing oil intensity. The chart below tells the story:

In his words

| Perhaps the single best macroeconomic gauge of oil-related “pain” at the EM-wide level is the cost of total oil consumption as a share of emerging GDP (the green bars in the chart). If that share is rising sharply, oil is crowding out spending and growth in other areas; if not, then oil is not really a threat. ...[In fact] the real GDP intensity of EM oil consumption may be declining on trend... Put another way, many investors wonder how economists can be sanguine about prices of US$110 or US$120 per barrel today when levels of US$60 to US$70 used to be seen as a big step six or seven years ago. For emerging markets, at least, the explanation is that today’s US$120 price of crude is essentially the same as US$70 was back then.” |

In other words, for all the headlines about the havoc – on terms of trade, inflation trends, fiscal position and the business cycle, more generally – caused by high oil prices, on average, emerging markets can take much more pain, in headline GDP terms. It’s an about-turn from 2008, the historical post-1980s peak in annual EM oil consumption/GDP at 8%.

There are two fat caveats to Anderson’s call:

| The first is that we’re ignoring the effects on the developed world, where there is of course no longer any growth in underlying deflators, and thus where sharply rising oil prices could have a more serious impact (offsetting the lack of nominal growth, on the other hand, are the facts that (i) relative consumption levels are lower in DM to start with than they are in EM, as a share of GDP, and (ii) absolute consumption has also fallen along with the crisis-related fall in economic activity). And second, when we talk about “EM-wide” effects we are glossing over intra-EM distributional effects on individual economies – which, as most readers are aware, are not small in key cases. |

But, put simply, high oil prices at current levels are not by themselves enough to derail the emerging market growth story.

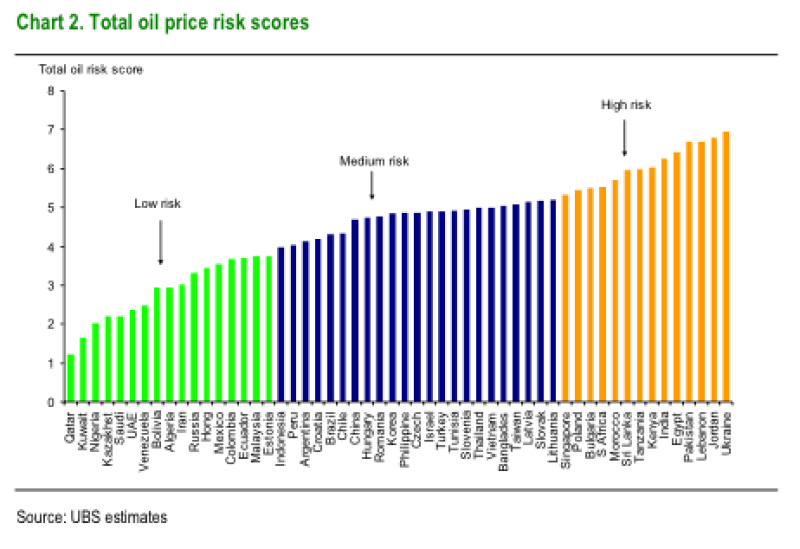

Of course, there are large regional variations, with net oil importers in India, Egypt and most of emerging Europe adversely affected, as this chart makes clear:

Market consensus is that the monetary implications of elevated commodity prices are, in theory, clear: central banks in oil-importing economies have less room to cut rates to stimulate growth given the inflationary impact of high oil prices. However, it’s an inexact science, as Demetrios Efstathiou, strategist at Royal Bank of Scotland, explains to Emerging Markets:

| "The relationship between high oil prices and inflation/currency trends is not always straightforward since it depends upon many factors, including whether oil imports will affect the domestic consumption of other goods in the economy or whether oil imports are used by export-oriented manufacturing sectors and the extent to which manufacturers can pass on the impact of high oil prices onto end-buyers." |

In EMEA, the Russian rouble and Kazakstan tenge – which is a managed currency – are the only real winners. According to RBS, those emerging European oil-importing economies most affected on a terms of trade basis by the marginal increase of oil prices from $75 to $115 per barrel are Ukraine, Bulgaria, Poland and Hungary while Romania and Turkey are relatively less affected.

For those investors that reckon emerging markets are principally a leveraged play on developed market growth, the market implications of stubbornly high oil prices are clear: Underweight EM assets, if you reckon high oil prices will savage European and US economies. But within the EM asset class, investors might short assets of oil-importers and adopt long positions toward oil exporters, if valuations are sufficiently compelling.

That said, there are two other potential consequences of high oil prices on emerging markets to mull over:

- A high oil price often fuels food price rises - by raising food production costs and biofuels consumption – increasing the chances of interest rate hikes to confront these inflationary pressures.

- High oil prices will prove a boon for Gulf exporters who have deployed their fiscal surpluses of recent years on their restless populations.

So overall, it's a pretty complicated set of effects with all to play for. But the likelihood is that the markets and currencies of oil importers are set to underperform their exporting peers, even if prices don't pass the pain threshold of Anderson's $135pb (or wherever else you peg that).