Monetary policy wonks, this one’s for you. The Fed’s announcement this week of a 2% inflation goal - capping off Bernanke’s seven-year price-setting mission - is historic. The world’s most important central bank, for the first time, is now bound to a single, specific inflation objective that is in the public domain and designed to survive Bernanke’s tenure.

(For the necessary caveats on why the Federal Reserve has not implemented a formal inflation-targeting framework, check out Andrew Lilco, a financial blogger for the UK’s Daily Telegraph.) But what does this mean for EM central banks, whose historic relationship with the Fed, can be roughly summed up as a historic master-slave relationship. In short, when the US cuts, emerging markets have traditionally followed, and vice-versa, thus, making EM rate hikes in the 2009 to H1 2010 period – when the Fed continued to ease via asset purchases – notable by virtue of its independence.

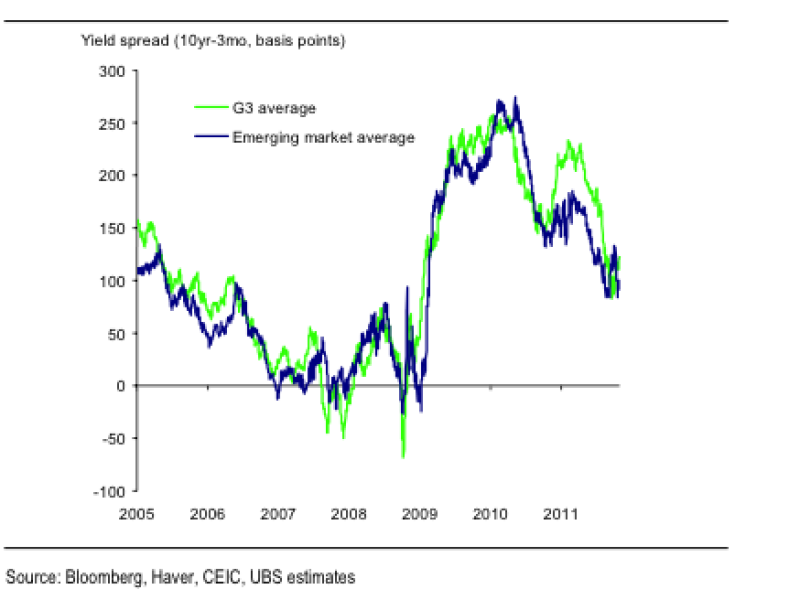

As these UBS charts – showing the average local-currency yield spread (10-year government bond yields less 3-month interbank rates) in the G3 compared to the average spread across 25 major EM economies – lay bare:

|

But, in a sense, roles - with the Fed setting the monetary agenda - have reversed somewhat since inflation-targeting frameworks, of sorts, have been implemented in a slew of developed and emerging markets for many years now. The Fed is now "probably a servant of history rather than its master," David Lubin, chief emerging markets economist at Citigroup, tells us.

In fact, the timing of the Fed’s flirtation with inflation-targeting is ironic, since it sits awkwardly with the fact that price-setting dogma has taken a knock in the global crisis (read: the ECB’s price-stability fetish that led to a rate hike in July 2011 even amid the debt crisis). First, in September 2010, an IMF working paper, penned by chief economist Olivier Blanchard, shocked global markets – given the policy lender’s history – by suggesting central banks should aim for a higher level of inflation in "normal times in order to increase the room for monetary policy to react to such shocks". Central bankers might want to target 4% inflation, rather than the 2% goal that is basically the case now – and the Fed’s newfound target this week - the IMF paper said. Aiming for higher inflation in good times would give policy-makers more juice to cut in lean times, it argued.

Another challenge to the efficacy of inflation-targeting regimes, and specific to EM, is the fact that the post-Lehman rout laid bare how growth concerns are all too often sacrificed on the altar of price stability during crises, increasing the relative appeal of old-school exchange-rate targeting, according to Lubin.

Over to you, David:

| The post-Lehman world made central bankers very sensitive to things that affect growth rather than things that affect inflation. Conversely, during the risk-on period and subsequent currency appreciation pressures, a number of EM central banks were worried that excessive EM FX would do unacceptable damage to real economic activity, and policy measures to redress this were enacted. In short, the purity of inflation targeting was replaced with a less pure concern with the level of exchange rates rather than the level of the inflation target. What’s more, emerging markets’ central bank obsession with exchange rates has been sustained since September when many EM central banks threw dollars [into their financial systems].

And now, as central banks see their currencies starting to strengthen again you can see easing is now [in vogue] with the Israeli rate cut clearly orientated to weakening shekel while Hungary decided that a rate hike would cause the forint to strengthen to unacceptable levels. |

In other words, currency objectives are still hard-wired into EM central banks' mentality - potentially, overriding inflation concerns - even among those that profess some sort of price-orientated mandate.

For the hawks, the speed at which EM central banks have cut rates in recent weeks in response to FX/growth concerns might underscore how they are still biased towards growth, at the expense of inflation. The jury will no doubt be out on whether that is, indeed, a bad thing.