With her trademark gele headscarf and blunt honesty, Nigeria’s finance minister, Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, is in many ways the face of Nigeria’s growing economic self-confidence.

The former vice-president of the World Bank – and public applicant for the institution’s presidency – has long been a fixture on the world stage, and has taken on much of the mantle of representing her country internationally, talking up the strengths of sub-Saharan Africa’s second-largest economy.

Back home, public protests, dwindling finances and political instability in the north are heaping pressure on Goodluck Jonathan, the ‘accidental president’, who came to power in 2010 when his predecessor, Umaru Yar’Adua, died in office.

In 2011, Jonathan won a second term and quickly assembled a powerful cabinet, bringing Okonjo-Iweala back from Washington DC as finance minister. Former Goldman Sachs managing director Segun Aganga, after a period as finance minister, became minister for trade and investment. Renowned agricultural economist Akin Adesina became the minister of agriculture and rural development.

With the personalities came a new impetus for reform across some of the most critical – and politically sensitive – areas of Nigeria’s economy and society.

“There have been a lot of things promised, but this time it does have a feel to it that if this particular team can’t push it through – if the technocrats in government can’t get it right – then you really wonder if there’s ever going to be a time that reform succeeds,” says Razia Khan, head of Africa research at Standard Chartered and a seasoned Nigeria analyst.

Even so, she says, there is a sense of positivity that has been engendered by the new technocratic cabinet, and by an apparently successful effort, beginning in late 2009, to clean out the notoriously corrupt banking sector by the central bank governor Lamido Sanusi.

Nigeria is Africa’s largest oil exporter, but a chronic lack of refining capacity means that it still imports much of its refined products. These are heavily subsidized at the point of consumption, and the monitoring has in many instances been weak.

A July probe by a presidential committee showed the scale of fraud within parts of the supply chain. As much as 382 billion naira ($2.4 billion) was allegedly collected in subsidy payments by oil marketing and trading companies in the previous 12 months – without the oil then being delivered. To add to the budget woes, the Nigerian National Petroleum Company (NNPC) said in July that it was owed around 1,134 billion naira in subsidies.

The subsidy is a serious drain on the national account – representing some 30% of all state expenditures. So far this year, more than half of the 888 billion naira set aside for it has already been disbursed. Any attempt to spend more than the allotted amount could face a legal challenge from the country’s powerful state governors, while an announcement of an end to subsidies earlier this year prompted street protests that forced a climb down.

The oil companies at the heart of the scandal have not been named, but local sources point to businesses well integrated into Nigeria’s political patronage networks, which will not be dismantled without a fight.

HIGH AMBITIONS

The Petroleum Industry Bill (PIB) has been in legislative limbo for the past four years – although its predecessor dates from the turn of the millennium. It proposes massive changes to the status quo, reforming taxes and royalty payments, imposing transparency across the industry, dictating the participation rates of local players in the industry and rebuilding the NNPC. The government’s vision is to turn the NNPC into an international player on the model of Brazil’s Petrobras or Malaysia’s Petronas.

The ambition to build a state enterprise that can operate oil fields and not only partner, but compete with, international players is a common trend across the continent, according to Brian Menell, a natural resources expert who has advised African governments on the creation of such entities.

“There are models like Petrobras or Saudi Aramco which are enormously credible, but [most governments] are a hell of a long way away from having the political capacity to create institutions with the degree of independence to have a depoliticized stature as corporatized state entities,” Menell says.

“They want something they can control completely that is a tool of the presidency in most instances, that can be empowered technically and financially to be a proper partner with confidence with foreign investors. And in most instances, they want it to be an operator.”

While some – such as Sonangol, the national oil company in Angola, Africa’s second-largest oil company – have been able to make the leap into limited production, Menell says these are the exception rather than the rule.

“There’s a great deal of naivete with respect to what it takes to be an operator. Making that leap from being strong junior partners to international operators, to being operators is one they all want to do, but very few will do,” he says.

In an attempt to prevent the leakage of resources from the Excess Crude Account and to ensure that Nigeria makes longer-term investments in its future, the government is also establishing a sovereign wealth fund. This process has been politically difficult, but appears closer to fruition than ever before.

At the end of August, former UBS and JP Morgan executive Uche Orji was appointed as the fund’s managing director and chief executive, with Alhaji Mahey Rasheed, the former deputy governor of the central bank, installed as chairman.

For the domestic economy at least, the true opportunity may not be oil, but gas. Nigeria’s gas reserves are estimated at more than 180 trillion cubic feet – enough to supply the European Union for over a decade. However, the country has failed to exploit the resource for export or for domestic use – denying itself foreign exchange and a relatively cheap source of fuel. The defining image of the Nigerian oil industry is that of the gas flares waving like flags over the Delta marshes.

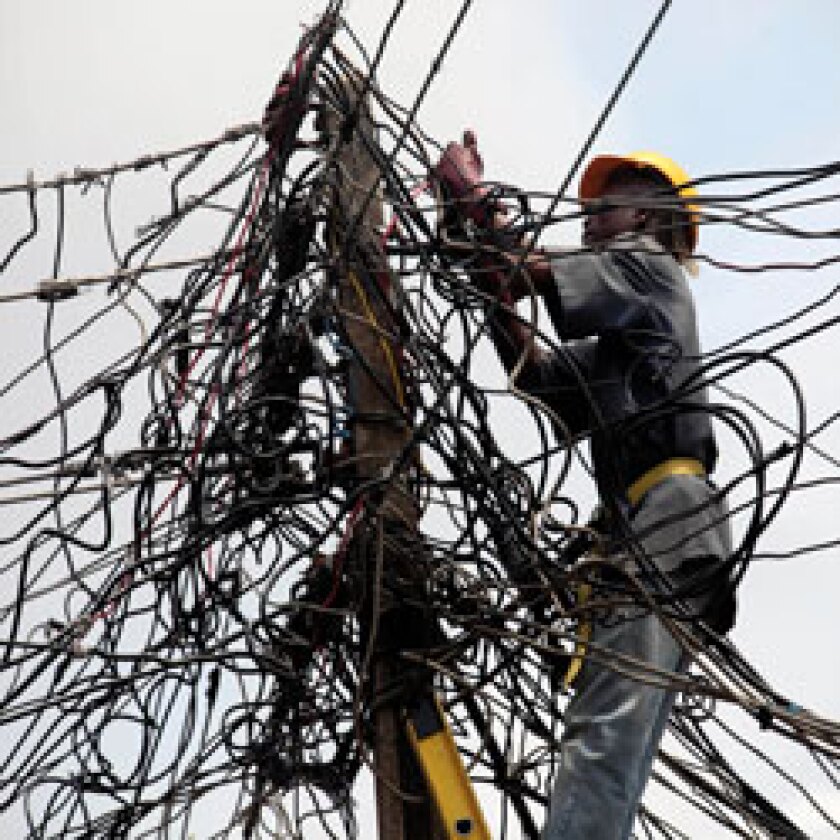

It is here that the PIB is interlocked with other elements of the country’s reform agenda – particularly the perennial attempts to crack Nigeria’s undersupply of electricity, which remains a huge drag on growth. Nigeria has one of the lowest per capita energy usages in Africa – a remarkable statistic given that it is the second-largest economy south of the Sahara.

Many of Nigeria’s small – and even larger – businesses run on imported diesel fuel. Only around 45% of the population has access to electricity, and only around 30% of their power demand is being met, according to statistics from the African Development Bank.

PRIVATIZATION HOPES

A supply of cheap gas into homes and businesses, and into gas-fired power stations, could mitigate the need for such huge subsidies. This is where former power minister Barth Nnaji’s reforms were to come in. Nnaji himself once ran an independent power producer in Nigeria and was tasked with liberalizing the sector.

However, with two months to go before the preferred bidders in a privatization process that was due to boost the power sector were to be announced, Nnaji resigned. He did not comment on his reasons, but local press and agencies said he did so to end allegations that his involvement in one of the companies bidding for state assets represented a conflict of interest.

The model to be emulated by the reforms is the telecoms sector, where international players bidding for licences in the privatization of a moribund industry ultimately created a thriving, highly competitive industry. Prices have dropped significantly, bringing mobile telephony into the reach of millions of consumers.

A total of 11 distribution and six generation companies are due to be sold off. The government will finance guarantees for investors, and hopes to raise between $600 million to $1 billion through an infrastructure bond, Okonjo-Iweala said in London in August. The country has also obtained a $150 million financing facility from the African Development Bank. Memoranda of understanding have been signed with international technology companies, including GE and Siemens, as well as Brazil’s Eletrobras and Korea’s Daewoo.

To make the privatization initiatives more compelling for investors, the cost of electricity to the consumer, which had previously been set low by the state monopoly, was raised in June.

“The problem with a lot of these reforms, and what makes them especially difficult, politically, is that the costs are borne up front,” Standard Chartered’s Khan says. “So you’ve got higher electricity tariffs to make the power-sector reforms more doable. You’ve got higher fuel prices. But the benefits of putting the reforms in place are things that will only be felt over the medium term.

“That creates greater uncertainty where anyone pushing forward with the reforms, given that cost-benefit structure and the lag in which the benefits will be felt, is going to have to be in a very strong place politically.”

This means that so much of Nigeria’s reform agenda – and hence its political future – is tied up with the personalities in the cabinet.

“With Ngozi, you wouldn’t find many people with more reformist credentials,” Khan says. “You feel that if she had the political power she would absolutely be doing the right thing and putting the right reforms in place; [the same goes for] the agriculture minister [Akin Adesina], who comes across as very impressive and was seen as a key technocrat when his appointment was announced.

“And in a sense you do have these very strong personalities, but the problem is that personalities alone don’t do anything for institutional change, and that’s where we really need to see more progress in Nigeria’s case.”

Others are still less positive about the potential for meaningful success. At the Council of Foreign Relations in New York, John Campbell, the former US ambassador to Nigeria and a long-term observer of the country, points out that, despite her international credibility, Okonjo-Iweala lacks a domestic political constituency, and has been a lightning rod for public anger after the attempt to remove the subsidy.

Continuing religious tensions in the north of Nigeria, where the Islamist militant group Boko Haram has exploited economic inequality, along with the end of the ‘zoning’ agreement – which had seen north and south rotate to provide a presidential candidate for the ruling PDP – has increased the sense of alienation among northern elites that are able to block reform.

“The real question I think is the extent to which there is a political will among the political elite to actually carry through reforms, and whether the reforms are even possible, given the current state of northern alienation,” Campbell says.

“When we’re talking about a political system where the arrangements and the relationships are built on money and where the money basically comes from the government’s control of oil, a meaningful anti-corruption campaign becomes in a sense quite destabilizing,” Campbell says.

“Now, all of this means, it seems to me, that the latitude for the Ngozis or the Sanusis of this world is constrained.”